- Home

- Yair Assulin

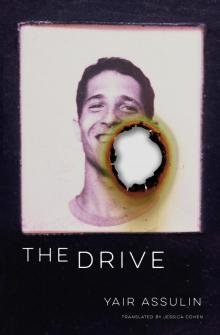

The Drive

The Drive Read online

www.newvesselpress.com

First published in Hebrew in 2011 as Neseah

Copyright © Yair Assulin

Xargol Books and Modan Publishers

Translation Copyright © 2020 Jessica Cohen

With support from “Am Ha-Sefer”—The Israeli Fund for Translation of Hebrew Books, The Cultural Administration, Israel Ministry of Culture and Sport

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Assulin, Yair

[Neseah. English]

The Drive/ Yair Assulin; translation by Jessica Cohen.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-939931-82-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019940460

I. Israel—Fiction

“In the army they don’t teach you how to kill; they teach you how to get killed.”

YEHUDA JUDD NE’EMAN

“It is my political right to be a subject which I must protect.”

ROLAND BARTHES

CONTENTS

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

CHAPTER ONE

I.

The Coastal Highway was hazy. The sun had not yet fully risen, and the light that emerged from the mountains and descended to the sea was pale and gray. Dad’s face was tired. Soon he would start calling people to cancel meetings. He would apologize, explain that “something came up,” say “I have to . . . ” or “I can’t make it because . . . ” and pause for a moment, then make up an excuse. I could sense him hiding the fear in his trembling voice, which was weary from a sleepless night. I could sense him trying to project, as he always did, that it was business as usual, “just a little matter of . . . ” When they pressed him and asked if anything was wrong, he insisted that it was nothing serious and signed off with a long “all right” and “take care” and ended the call. Then the car was quiet, a silence that under different circumstances one might have described with pretty words such as “wonderful” or “thought-provoking” or “genuine,” but which now was merely the silence of exhaustion and tension gnawing away at one’s stomach.

Before leaving Haifa we had the radio on: first Israeli folk songs, then sleepy chatter about the previous day’s events. The things that happened yesterday, I thought to myself. And where am I among those things? Why aren’t I there? The deep voice on the radio spoke of a woman whose husband had killed her with a knife, stabbed her repeatedly in front of her children, and about Maccabi Haifa who’d won the national championship cup again, and about a Belgian pilot who’d circumnavigated Europe in an airship. Then someone talked about how perhaps a war would break out and perhaps there would be peace, but only perhaps, because at present there were too many factors “hindering progress.”

How pathetic, I thought. How stupid. Always some shard of veracity that sneaks in through the back door of the radio and turns into reality for us all: “the news.” And what about my reality? What about the reality of last night? I looked at the sea, where the waves were crashing furiously as if they were partners to my pain. Because last night I banged my head against the wall at least fifty times and cried like a baby, and then we stood there in my room, the three of us, Mom and Dad and I, and Dad almost cried, in fact he really did cry, and Mom held him and hugged me, and she too, like me, had cried earlier and her face was damp. Isn’t that good enough news for the radio? That’s what I thought as I kept looking at the gray sea, which kept crashing against the breakwaters along the coast.

Then I saw a silver-colored car parked by the beach, and for a few moments I allowed myself to imagine the couple that might have been sitting inside it. Her head was probably resting on his lap or belly, and the seats were probably pushed back, almost all the way down, and she was whispering to him that she loved him, or the other way around, being quiet while he told her he loved her. Or perhaps he’d already told her that too many times, I thought, and I imagined her saying nothing upon hearing those words that he repeated over and over again in order to hear an answer that never came. And then I thought of Ayala. I can’t remember what state we were in back then, when I took that drive. It was a long time ago, and it had been unclear for quite some time whether we were really together or just stuck in a distant relationship that sometimes felt like a body slung over my back and at other times like the only thing that existed in the world. And how seldom were the times when it seemed like the only thing in the world.

I remembered that night we slept in my mom’s car at Lake Kinneret; I remembered the sun beating down on my face in the morning and my headache that got worse and worse, like a nightmare, when I kept turning my head back and forth, trying to get away from the sun and sleep a little longer—anything but wake up. I remembered how at some point I gave up on sleep and opened the door to breathe in the fresh air. And then I saw her standing there on the shore, wrapped in a white blanket, gazing at the water. It was hot, and the sun had already risen quite far, but the sky was gray exactly as it was on that drive with Dad: a sky the sickly color of faded work pants. We stood there looking out at the water together, silently, and after that we broke up for a few weeks.

I remembered a conversation we had before I joined the army. She said she was afraid I’d go crazy, that our relationship would die when I was in the army because we’d stop being together. Then I remembered that we had that conversation right here, just outside Haifa, near the spot where I saw the car parked by the beach. I think there was a sand sculpture competition on the beach that day, and we went to see a statue of Buddha that everyone was talking about—a fat, smiling Buddha. I remember Ayala in big, black sunglasses, holding my hand, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that I was holding her hand, and she talked about how afraid she was, without looking at me.

“Maybe we should end it now, before you go into the army,” she said. “You understand that afterward it’ll be a lot more painful, for both of us.” She always pulled out those clichés and said them with a serious expression, the sort of lines that gave her that Tel-Aviv-New-York-intellectual tone that she was so fond of, like a character in a Woody Allen film, always in a confident voice, the kind used by someone who knows everything.

I was also decisive when we talked on the beach. I also used pretty words and talked about “love” and “coping with crises” and what we “need” and what we “don’t need.” But that morning, when I took the drive with Dad, sitting next to him in the car with my knees clasped together like a little girl who has to go potty, I derided myself for being so decisive, and for the clichés. “If we really love each other, that should be enough, shouldn’t it?” I asked her. “How can we break up when we love each other? Are you saying we’re going to break up every time things get hard? There are always situations like this in life, like the army. And if you love me the way you say you do, then we have to go on. Besides, everyone gets through it, don’t they? Are you saying everyone who goes into the army just gives up everything?”

What arrogance, I thought on that drive, to talk about the army as if it were something familiar, something known, something “everyone goes through.” I admonished myself: Had you ever been through anything like the army when you said those words to her? I found solace in a segment of orange that Dad handed me as he drove, and in his face, which contained, beyond disappointment and sadness, the familiar lines of love. Have you ever even been in that situation, or one like it? A situation in which your d

esire doesn’t matter at all, where you’re constantly being told what to do, when to eat and when to sleep and when to run and when to talk on the phone, and even when you’re allowed to take a shit or a piss?

I remember my first month in the army, in basic training, when I was on the bus with my platoon sergeant and I didn’t know if I was allowed to eat a piece of candy I had in my pocket, because they told us we weren’t allowed to eat anything without permission, not even candy. I remember that I deliberated for a long time about whether or not he would notice me eating it, and what would happen if he did. My desire to take comfort in the candy, coupled with my fear of being punished if he caught me eating it without permission, drove me to ask him if I was allowed to. I can hear my fragile voice, my failure to comprehend that this sergeant was only slightly older than I was, and that he too was a soldier who just wanted to finish his service and go back to being a normal human being. “Sergeant, can I have a candy?” I asked. “No. Why would you?” he answered immediately in his cutting, nasal voice. I think again about my arrogance before enlisting, about the entirely unfounded confidence, perhaps even the repression of what was about to happen, and again I am filled with the shame of failure.

And I think about Ayala again. Her face was thin back then, and I remember her prominent cheekbones, her short black hair and white skin, her lips pursed dubiously when we talked on the beach that day, among the statues, when I said that the army was something everyone had to get through so we shouldn’t make such a big deal out of it, and that love was the most important thing. Then I remember her kissing me.

II.

Dad turned the radio back on. I remember how once, when I was in elementary school, he picked me up from one of those after-school activities I used to enthusiastically sign up for at the beginning of every year and stop going to after a few times, and he taught me a biblical verse: “Let not him that girdeth on his armor boast himself as he that putteth it off.” To this day I can hear him explaining what those words meant, and the story sounded so wonderful to me: “‘Him that girdeth on his armor’ is the soldier preparing for war, who doesn’t know if he is going to win or lose. And ‘he that putteth it off’ is the soldier who comes back from war after winning.” I remember picturing a soldier going off to battle, like King Saul, and a soldier returning triumphantly, like David. In those days I knew “David’s Lament for Saul and Jonathan” by heart, and each evening I would ask Mom to read it to me from the Children’s Bible. I think of how my soul thrilled every time I heard anything about armies and wars and victories.

Now the word army makes me nauseous. I remember the many occasions when Dad reminded me of that verse. One of the last was when I talked about how I was going to become an outstanding warrior, and I pictured myself with my buzz cut and my brawny body, marching through all sorts of dark places, and the glory that would follow, especially among women.

Once, just to see her eyes fill with worry, I even described to Mom how the notification officer would knock on our door at two a.m. to inform them of my death. She got mad and yelled at me to stop. I didn’t just do it to Mom, I also did it to Shlomit, whom I loved very much at the time, and for the same exact purpose: to see the worry flood her blue eyes. And I remember Dad telling me in a reproachful voice: “How many times must I recite that verse for you? ‘Let not him that girdeth on his armor boast himself as he that putteth it off.’”

III.

The car coasted along the empty highway to the Mental Health Officer at Tel Hashomer Hospital. “Tell me what you want,” Dad had said the night before, in tears, after I’d cried for perhaps an hour without stopping and said I couldn’t go on, that I felt as if I were suffocating, that I’d rather die than go back to the base. “Just tell me what you want,” he repeated, “what do you want to do? What do you want to happen?”

“I don’t know,” I answered. “I don’t know, I really don’t. I just know that I don’t want to go back there. I don’t want to.”

“But what is it that’s so terrible there?” he asked for the millionth time since I’d first cried over the phone, and I knew that someone looking from the outside could not even begin to comprehend the suffocation that filled me each time I took the train to the base, the insurmountable pain I felt when I walked through those gates, the fear of something I cannot describe or define, the horribly cramped sensation that was unrelated to anything, certainly not to a particular place or space. Again I told him that I was miserable. Again I told him that I felt I was losing myself. A few days earlier I’d told him I wanted to jump in front of oncoming traffic. I didn’t want to die, I just wanted some time off, a little time to calm down.

Now I remember that picture clearly, of how I stood on the side of the dilapidated road outside the base and there was mud everywhere. I remember the headlights of a distant car approaching, and the feeling that this time I was serious, this time I was really going to do it. I remember the voices in my head that told me I’d already said that so many times, and I remember the insistence in my mind that this time I had no choice, I was going to jump, and even if I died I didn’t care. Then I envisioned Mom and Dad’s faces, and I heard Mom’s voice, which had been slightly high-pitched when I’d called a few days or a week earlier and burst into tears when I said I couldn’t take it anymore.

I was on a different base then, near Nablus. The whole unit was on that base, which was full of tents and surrounded by giant concrete walls, long lines of massive gray blocks. I walked around for a week feeling as if I were going to suffocate. All I wanted to do was shut my eyes and sleep. It was winter and the work was exhausting: sitting in the war room listening to the phone. It wasn’t dangerous, I know, not dangerous like driving in the middle of the night in a black Audi to arrest a wanted person in a village, or like sitting at a lookout post in the middle of nowhere when someone could put a bullet through your head at any minute, or like actually fighting in Lebanon or Gaza. But for me, it was soul-crushing. It wasn’t just the work but all the people who hung around those big rooms full of telephones and supposedly important conversations, and the horrible feeling that you were insignificant. That you were nothing. That you were but one more instrument on the desk, like the pen or the computer or the old, encoded phones. Sometimes I had the feeling that I wasn’t even an instrument, that in fact I hardly existed, that I had to do everything for someone who did everything for someone who did everything for someone, and sometimes I had the feeling that the ladder never ended but merely branched out endlessly and reeked and grew mold and became caked with mud.

That was how I felt on that base, but I know that even that doesn’t explain the phone call when I could no longer suppress my sobs as soon as I heard my mother ask how I was. Up until then I kept trying to sound as if everything was fine, there was no problem, I was doing all right. And that definitely was not a reason I could give Dad when he asked me, “What’s so bad there?” Because even that didn’t explain why things were so bad for me there—not the reeking ladder that never ended or the fact that I wasn’t important and didn’t exist, not even the dreadful fact that I did not have my own regular bed on that base, that a few of us shared what was called a “whore bed,” and every morning I had to strip my sheets off and shove them under the bunk bed in the big green dusty bag we were given at the induction center. Or that after a night shift I had to wait for someone to get up so that I could get some sleep until they came to wake me up and tell me I’d slept enough, or in fact not even wake me, because I was usually awake already and lying in bed with my eyes closed just to steal a few more moments of quiet, a few seconds in which I could think about Ayala, for example, and remember how a few weeks ago we’d had a wonderful conversation after we hadn’t talked for a while, or to think about the argument I’d had with Dror and about how I was right—to reanalyze the logic of my position and verify that I really was right. That was probably also not the reason for the phone call that dropped us into the whirlwind that eventually saved my life.

IV.

In the end I didn’t jump. Something gripped me by the calves and would not let me take that leap forward. I remember standing as the car passed me and kept going, unaware of the enormous role it would have been destined to play had I jumped. Then I thought about this matter of fate, and about how if I had jumped I might have died, and the driver might have gone to prison without truly being at fault.

I imagined the face of an army driver I knew. I imagined him as the driver of the car that had just gone by, and I imagined that I had jumped and he’d hit me. I imagined his face when he got out of the car to see what he’d hit, and his mouth opening to shout for help. I imagined his face at the inquiry and then in court, and I remembered a Rashi parable about an accidental murderer and a malicious murderer and how everything in the world falls into place, because “a reward shall be brought about by a meritorious person and a debt by the debtor,” but I couldn’t decide if by me not jumping, thereby preventing him from hitting me, he would end up with merit or debt. All these musings went through my mind in no longer than a few seconds, because immediately afterward, when I realized that now I had to go back to the barracks full of pathetic soldiers and officers who only cared about covering their own asses, I was once again flooded with that terrible feeling of suffocation and shortness of breath, and I prayed that another car would go by, but none did, the road remained dark. I headed back toward the barracks. I think it started raining and I hid under the asbestos shelter of a weapons depot.

The Drive

The Drive